Roots of f(f(..f(x)..)), f(x) = ax² + bx + c

Define $ f(x) = ax^2 + bx + c , a,b,c \in \mathbb{R}$ and $ f^n(x) = f(f^{n-1}(x)), n>1 $. Prove that the real roots of $ f^n(x) $ are symmetric about the vertical line passing through vertex i.e. $ x = \frac{-b}{2a} $

This seems like a complicated problem. Let’s start by first making intuitional sense of this problem. We can say that $ f^n(x) $ will be a polynomial of the order $ 2^n $ and will have as many roots. Also, all roots of a quadratic of the form $ ax^2 + bx + c , a,b \in \mathbb{R} $ can be expressed as $ \frac{-b}{2a} \pm k$, where $k$ is some constant, which can be real or complex. To find all the real roots of $ f^n(x) $, we have to solve the set of equations $ f^{n-1}(x) = \alpha_i \backepsilon \alpha_i $ is a root of $ f^{n-1}(x) $.

This problem can be recursively broken down until we arrive at finding the roots of $ f^2(x) $, which are the roots of $ f(x) = \alpha_1 = \frac{-b}{2a} + k $ and $ f(x) = \alpha_2 = \frac{-b}{2a} - k $. Since these two quadratics also assume the form in the paragraph discussed above, their roots can be written as $ \frac{-b}{2a} \pm u $ and $ \frac{-b}{2a} \pm v $. Note that if the equation has complex roots, then the values of u and v would be imaginary. This does not matter, as any further equations solved upon them will continue to have their roots expressed as $ \frac{-b}{2a} \pm k $. Moving to solve $ f^3(x) $ requires us to solve the equations $f(x) = \frac{-b}{2a} \pm u $ and $f(x) = \frac{-b}{2a} \pm v $. If we continue to do this, we can notice that all the $ 2^n $ roots of $ ax^2 + bx + c $ can be expressed in the same form $ \frac{-b}{2a} \pm v $, as the value of the first two coefficients of the quadratic(s) to be solved remains the same. Thus, all the real roots are symmetric about the said vertical line and all imaginary roots have their real part equal to $ \frac{-b}{2a} $. $ \blacksquare $

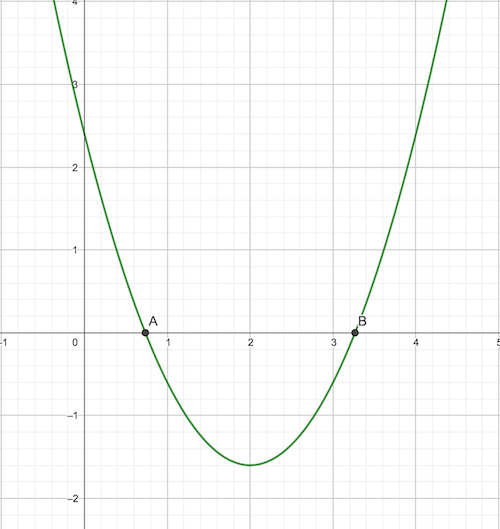

A graphical proof for this is as follows: consider any arbitary quadratic with two real roots (this can also be proven with a quadratic with no real roots, but that requires mapping the complex plane on the z-axis, which I don’t want to do).

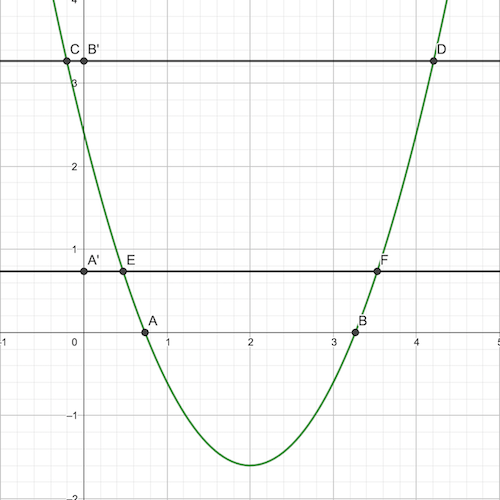

Here the roots are A and B. Reflecting them onto the Y-axis and drawing two parallel lines through them gives us the following graph:

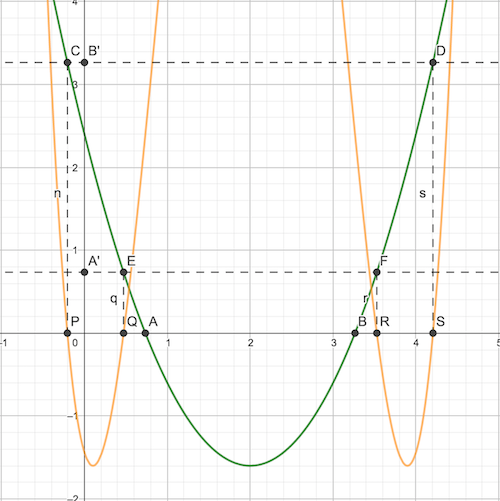

The two lines represent the roots and the points of intersection of the parabola with the line (That’s C,D,E and F) represent the roots of the equation $f^2(x)$. This can be verified by plotting $ f(f(x)) $ in the same graph

This provides a more intuitive approach to the above proof. As is clearly visible, $ f^2(x) $ has all it’s roots symmetrical. This procedure can be repeated $n$ times, giving us the requisite proof.

Both of my proofs are not very mathematically rigorous. A rigorous proof would involve induction using the principles I showed here. That exercise is left to the readers (mainly because my induction & formal proof-writing skills are horrible :P).

An application of this problem can be found in the PUMAC 2019 Algebra A paper, Q3. This is a rather nice problem, which involves the sum of the roots of $ f^n(x) $. Since all the roots are symmetric, you would end up with $ 2^n $ times the abscissa of the vertex of said quadratic.