This note on random variables follows as a result of confusing notation in several math textbooks. I’ll explain random variables (in measure theoretic terms) as verbosely as I can, and then prove some results. This article assumes that the reader is familiar with probability triples

1. Random Variable Prerequisites

We start with defining measurable spaces and measurable functions

Definition 1.1: A Measurable space

consists of a set and a -algebra defined on .

Definition 1.2: A Generated

-algebra is the smallest -algebra containing a specified collection of sets. That is, if is a set of subsets of , is the smallest sigma-algebra such that .

Definition 1.3: A Measurable Function

between two measurable spaces is a function such that for every , .

Since the definition

Definition 1.4:

NOTE: The above definition is confusing, but is unfortunately the norm when dealing with measurable functions. In the context of measurable functions,

Measurable functions can also be defined in terms of the

Definition 1.5: The

-algebra generated by a function is the collection of all inverse images .

According to this definition, if

2. Random Variables

Random variables are unfortunately, neither random nor variables. This is the first of many misnomers that we encounter in their study.

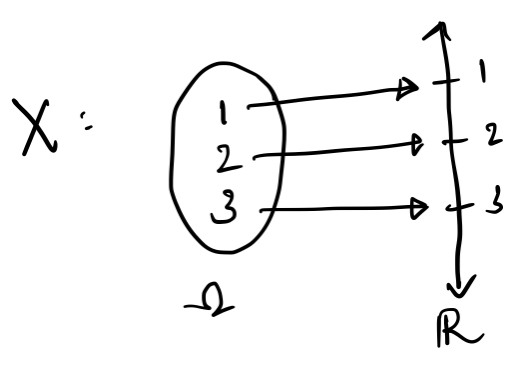

Definition 2.1: A Random Variable

defined on a probability triple is a measurable function

In it’s simplest terms, A random variable is simply a function from

Consider

such that

Now, suppose we had to calculate the probability that the random variable

Why then, do random variables need to be measurable functions? Note that the probability measure is only defined for sets in

An example for this is to consider

such that

3. Results on Random Variables

Claim 3.1: If

is a random variable on , then .

A simple (maybe even obvious) claim, the proof is by definition:

Claim 3.2: If

is the indicator of some event , then is a random variable

Proof: for all

The next two claims would be key to proving results about functions of random variables

Claim 3.3: if

and are two measurable functions, then is also a measurable function

Proof: For all

Claim 3.4:

is measurable if .

Proof: Note that

This above claim ensures that we don’t need to prove that every set of a

Claim 3.5: Every continuous function

is measurable.

Proof: from (3.4), it’s sufficient to prove that for every open set

The above three claims give us the following very powerful result: every continuous function of a random variable is also a random variable. We can make a stronger claim, after proving the following claims as well:

Claim 3.6: If

and are random variables on , then and are random variables as well

Proof: This cute proof comes from Rosenthal. It’s sufficient to prove that

Since all the elements in the union belong to

XY is also a random variable, as

We are now free to extend the claim that every continuous function of a random variable is a random variable, to piecewise continuity: every piecewise continuous function of a random variable is also a random variable. If

4. References

- Rosenthal, Jeffrey S. A First Look at Rigorous Probability Theory. World Scientific, 2006. Open WorldCat, http://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=5227675

- Lebanon, Guy, editor. Probability: The Analysis of Data ; Vol. 1. 2012. Available online at http://theanalysisofdata.com/probability/0_2.html

- Math StackExchange, Wikipedia, etc etc :)